Introduction

For this project, I selected data from the Kaggle Speed Dating Experiment. Feeling nostalgic for social psychology, I thought this data was a perfect representation of social science research. It was compiled by Columbia Business School professors Ray Fisman and Sheena Iyengar. The data “was gathered from participants in experimental speed dating events from 2002-2004. During the events, the attendees would have a four minute “first date” with every other participant of the opposite sex. At the end of their four minutes, participants were asked if they would like to see their date again. They were also asked to rate their date on six attributes: Attractiveness, Sincerity, Intelligence, Fun, Ambition, and Shared Interests.”

In addition, demographics, dating habits, self-perception across key attributes, beliefs on what others find valuable in a mate, and lifestyle information were collected at different points in time. See the Speed Dating Data Key document for details (click on View Raw to see the key).

The features were assessed at Time 1 (before and right after participating in the event), Time 2 (the day after participating in the event), and Time 3 (3-4 weeks after participating in the event). I only used the data from Time 1 because that was the only data that was relevant to my model since I wanted to predict the probability of leaving the events with a match for both males and females. The project had 4 parts: 1) data cleaning, 2) Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), 3) feature selection, and 4) model selection.

My goal was to find out what attitudes towards mating influences love at first sight as well as the probability of finding love at first sight at Columbia speed dating events. Because of gender differences in partner selection (Fisman, Raymond, et al., 2006), my decision was to build two models: a model for males and a model for females with dependent variable match. Thus, the first model predicted the probability of finding a match for males while the second model predicted the probability of finding a match for females.

Exploratory Data Analysis

The goal of the exploratory data analysis (EDA) was to investigate demographic data and to highlight gender differences in mate selection.

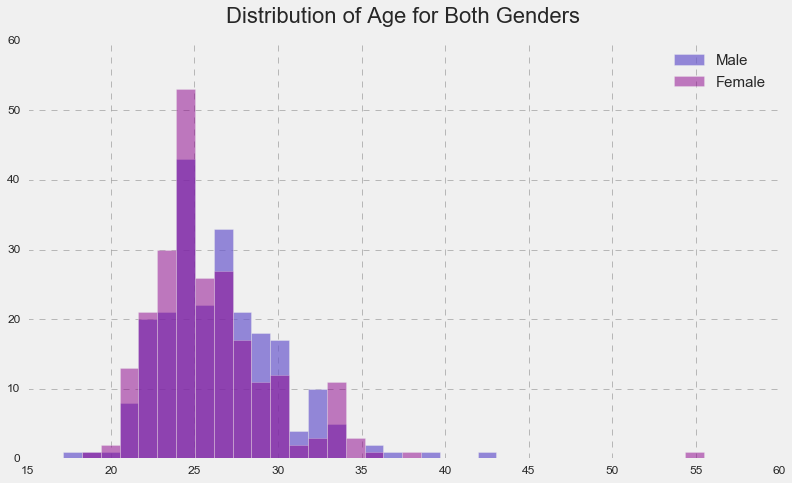

As we can see from the histogram, most females and males were in the age group of 20-35 with several minor exceptions. There were also a couple of outliers, a male of 43 y.o. and a female of 55 y.o.

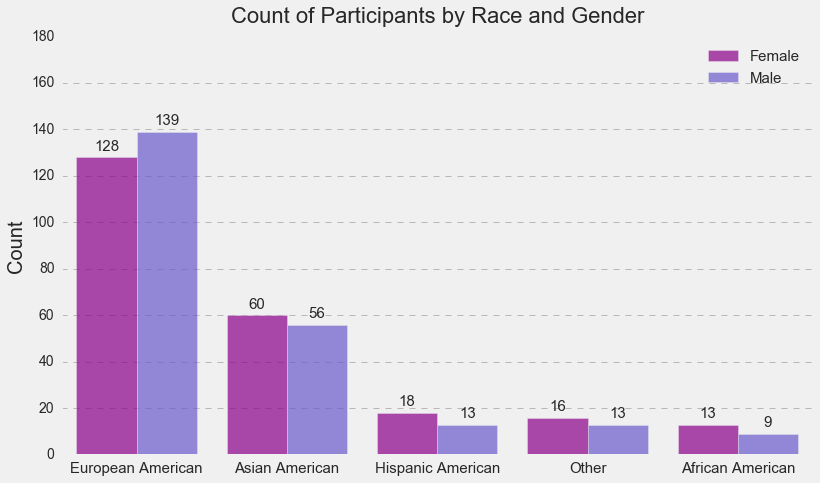

Most participants were European Americans, followed by Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, others, and African Americans. There was approximately the same number of males and females in each race group.

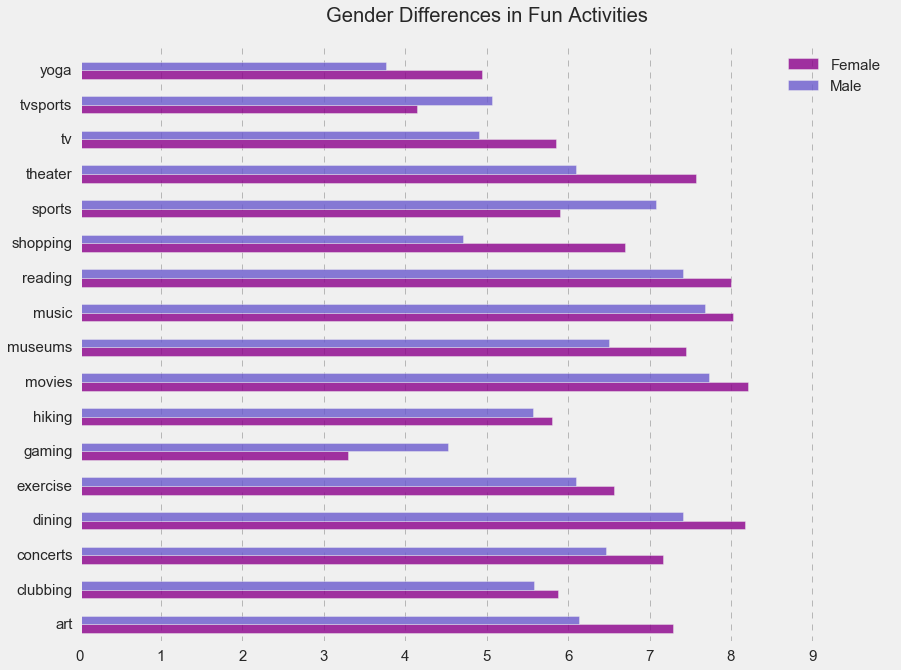

Furthermore, as seen below, there were some gender differences in recreational activities. Males were more interested in sports, TV sports, and gaming while females preferred yoga, watching TV, theater, shopping, dining concerts, and art. Both genders liked reading, music, movies, hiking, exercise, and clubbing.

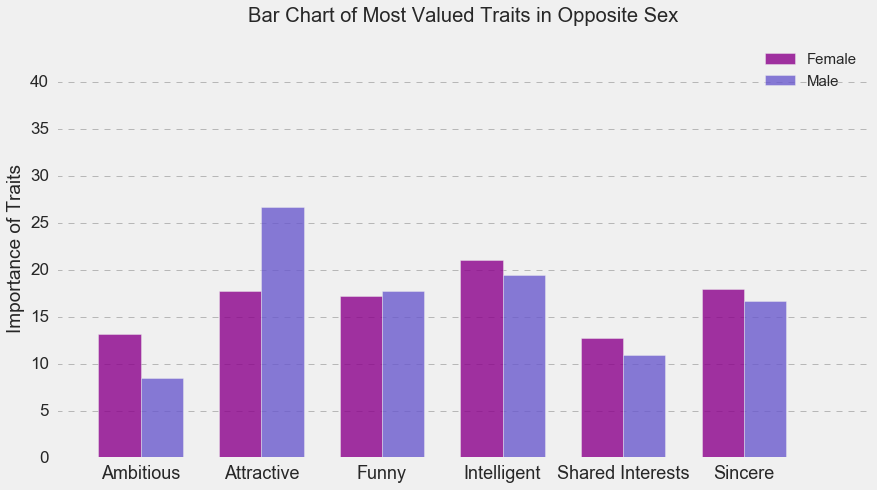

In spite of the gender differences, both genders equally valued funny, intelligent, sincere partners who share their interests. However, as shown below, males were more likely to value attractive females, while females were more likely to value ambitious males.

The EDA points out gender differences in fun activities and mate selection, confirming my suspicion that it is crucial to build two different models predicting speed dating match for each gender. Different features predicting match for males vs. females can affect the predictive accuracy of models.

Feature Selection

Feature extraction methods are important to create accurate predictive models. They help to choose features that will provide the best possible model fit with less data. The feature extraction process here was divided onto two parts.

In the first part of the feature extraction process (a preliminary feature extraction), I investigated separate effects of continuous and categorical features on dependent variables. Some of the categorical features consisted of over 100 categories, and there were around 60 continuous features in the dataset at Time 1. Because categorical features with many categories tend to mask the effect of continuous variables, to avoid the masking effect, I preliminary ran two feature selection models for males and females: 1) a model with continuous features, and 2) a model with categorical features. After I selected the most important continuous features and the most important categorical features, I implemented the second part of the feature extraction process. See the python code and output here for males and here for females.

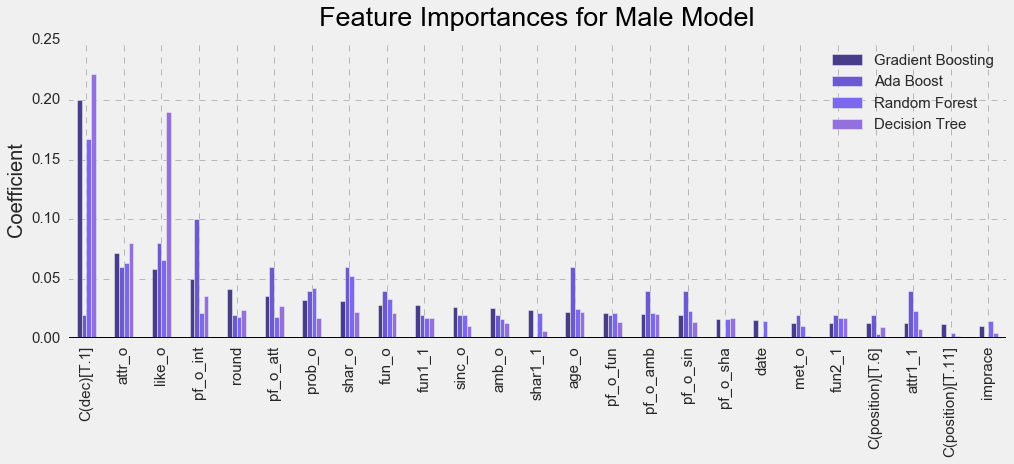

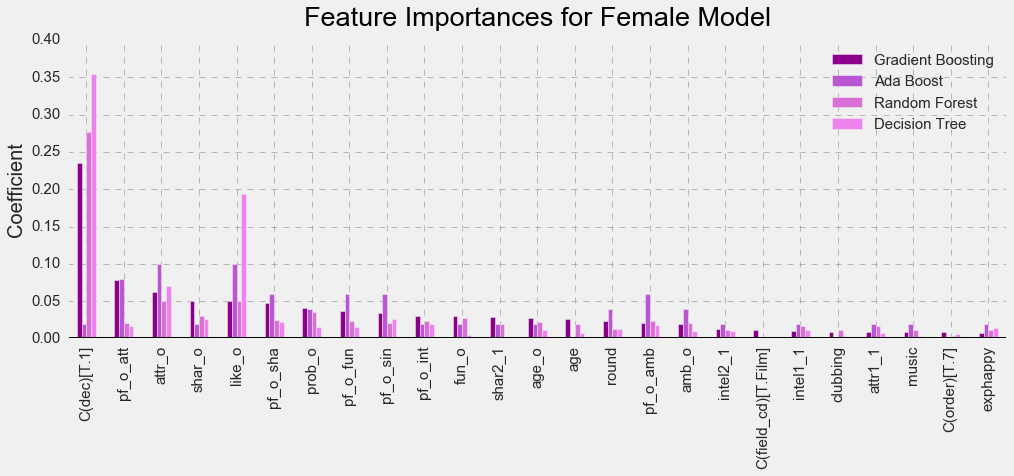

In the second part (the final feature extraction process), I combined the most important continuous and categorical features that were extracted in the first part and ran another feature selection model for males and females using the selected features. The features from the final feature extraction process for my final model were selected in a way that would produce the highest accuracy score across four machine learning classifiers: 1) Random Forest, 2) Adaptive Boosting, 3) Gradient Boosting, and 4) Decision Tree.

In addition to the feature selection algorithms, I used social science theories to select final features. For example, in order for a participant to find a match, the participant first and foremost should like his/her speed dating partner. Because the data did not contain an evaluation of the qualities of a given speed dating partner by the participant, I used the participant’s decision in my model (dec) to evaluate whether the participant likes his/her speed dating partner. In addition, the data also contained the evaluation of the participant’s qualities by his/her speed dating partner, demographics of the participant and his/her speed dating partner, and preferences in mate selection and fun activities by the participant and his/her speed dating partner.

I included in the models some variables that, at first glance, might not seem to affect finding a match. However, these variables could affect a participant’s psychological processes and, therefore, his/her decision. I deemed it was important to control for these features and included them in my preliminary feature selection process. Those variables were: 1) station number where partners met (position) since this can affect their mood and thus their decision, 2) condition (condtn) since some participants had limited choice 3) wave or date (wave) when the event took place, 4) a number of people met in each wave (round) because having met more people increases chances of finding someone.

I excluded unique partner’s id (pid) from the models, even though it predicted finding a match, since some individuals are more socially popular and more attractive, and hence they get more attention at dating events. I refrained from using partner’s id in my model as it would be hard to apply to a different set of participants. Their unique ids would affect predictive models differently.

I will go over only selected features as I don’t want to make this post very long. If you are curious about the ones I didn’t mention you can take a look at logistic regression outputs for the male model and the female model.

As seen above, it is very important for a male participant if his speed dating partner (female) finds him attractive (att_o), likes him overall (like_o), thinks he likes her too (prob_o), shares the same interests with him (share_o), and thinks he is a fun person (fun_o). Interestingly, finding your male dating partner sincere (sin_o) and ambitious (amb_o) negatively predicted finding a match for males. It seemed like sincerity and ambition did not help males to find love at first sight.

Age of partner (age_o) is also important for males to find their match, as is whether his speed dating partner has met him before (met_o), indicating that males tend to warm up faster to females they know.

How many people the male participant meets in a wave (round) and whether he is a frequent dater (date) also plays a large role in finding a match. The more people there are in a wave the more likely he was to meet his match. Frequent male-daters are more likely to get themselves a match. I know it is not fair but I suppose frequent daters are more experienced and hence seem more appealing to ladies.

In order for a female participant to meet her match, it is very important for her speed dating partner to find her attractive (att_o), share common interests with her (share_o), like her overall (like_o), think she likes him too (prob_o), and only after that is it important for him whether she is fun (fun_o) or whether she is ambitious (amb_o). Being ambitious negatively predicted finding a match for females at Columbia speed dating events, while sincerity (sin_o) was not even a consideration.

While age of partner (age_o) is equally important for females as for males to find their match (as reported by participants), only female age (age) negatively predicted finding a match. Basically, it means that females of older age had a much harder time finding love at first sight.

Replicating findings with males, the number of people in a wave (round) also positively predicted finding a match for females. Finally, major(field_cd) played a huge role in whether females would get selected for further dating. The most popular females among males were those who studied Film and Social Work compared to those females who studied Biology/Chemistry/Physics.

I included 21 features in the female model and 19 features in the male model. Those features would give me the best possible accuracy scores across the classifiers.

To be continued in Part 2

REFERENCES

- Fisman, R., Iyengar, S. S., Kamenica, E., & Simonson, I. (2006). Gender differences in mate selection: Evidence from a speed dating experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 673-697.